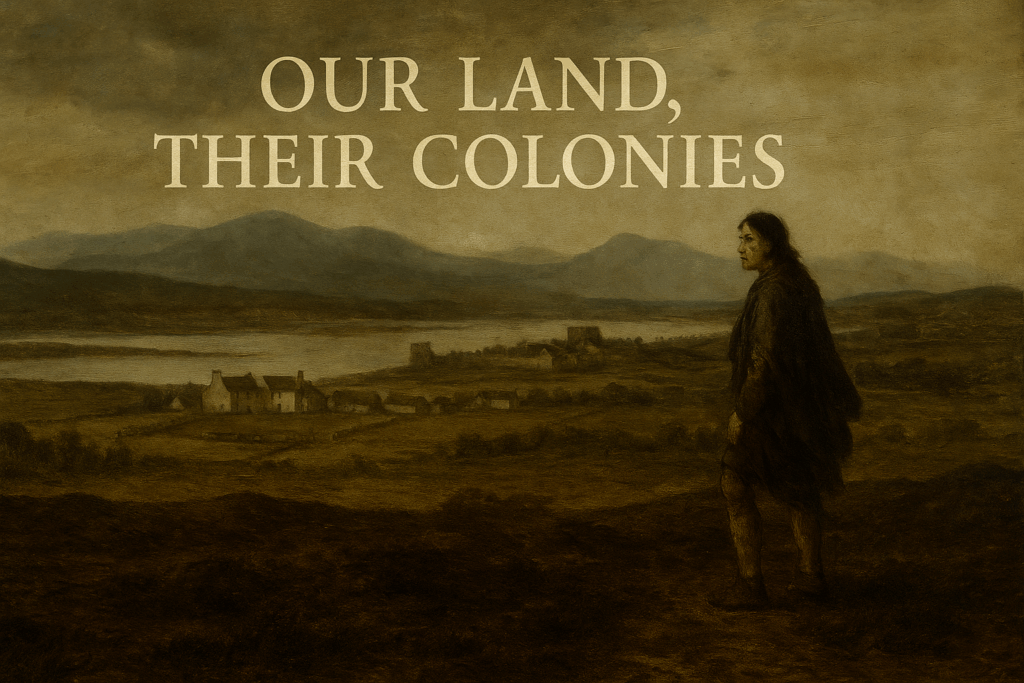

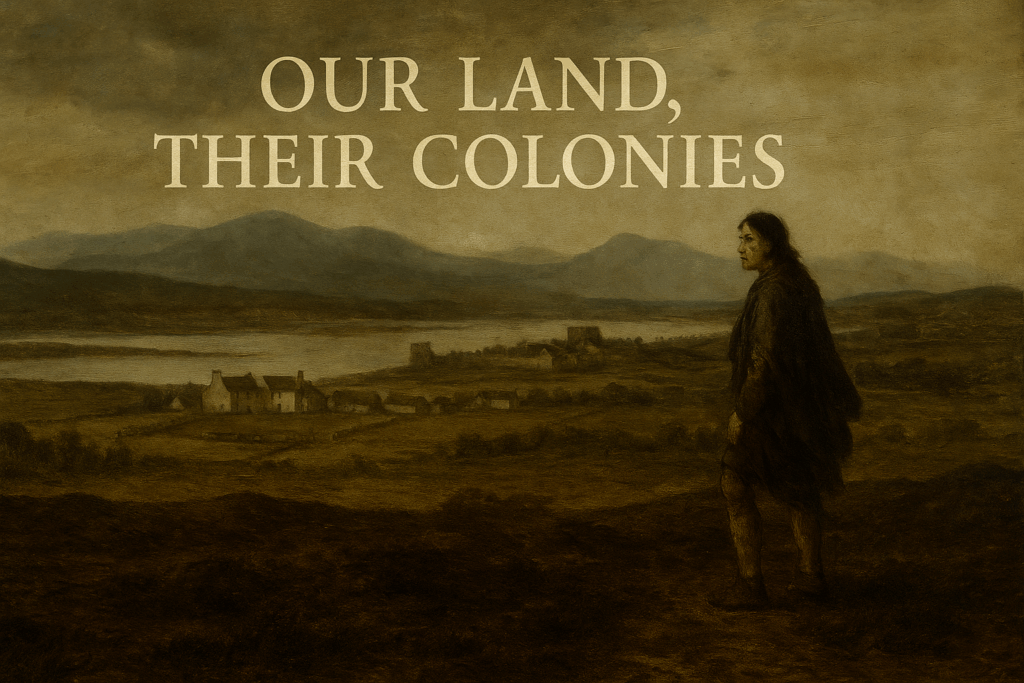

In the shadowed pages of Ireland’s history, few chapters run as deep with sorrow, resistance, and resilience as the Plantations — a calculated campaign of dispossession and colonization that scarred the island and altered its soul.

It was not a war for territory. It was a war for identity — for the language, the land, and the life of a people who would not kneel.

A Nation Carved Up

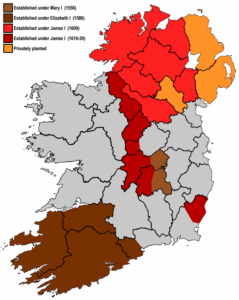

In the wake of England’s Tudor conquests of Ireland, beginning in the 16th century, a new colonial strategy was devised: Plantation. This was not agriculture. This was the systematic planting of English and Scottish Protestant settlers onto lands confiscated from native Irish lords — the Gaelic nobility who had ruled these hills and valleys for centuries.

The plan was brutal in its clarity: remove the Irish from their ancestral lands, and replace them with loyal subjects of the Crown. It was conquest disguised as order. Civilization dressed in chainmail.

The first major plantation, in Laois and Offaly (then called Queen’s and King’s Counties), was a prelude — a rehearsal for what was to come. But it was Ulster, the ancient stronghold of Gaelic Ireland, that would suffer most deeply.

The Flight of the Earls — and the Fall of Ulster

In 1607, after years of rebellion against English rule, the last great Gaelic chieftains — including Hugh O’Neill and Rory O’Donnell — fled Ireland in what would be remembered as the Flight of the Earls. Their departure was seen in England not as a tragedy, but an opportunity.

Their lands, rich and vast, were declared forfeit. By royal decree, Ulster was to be planted.

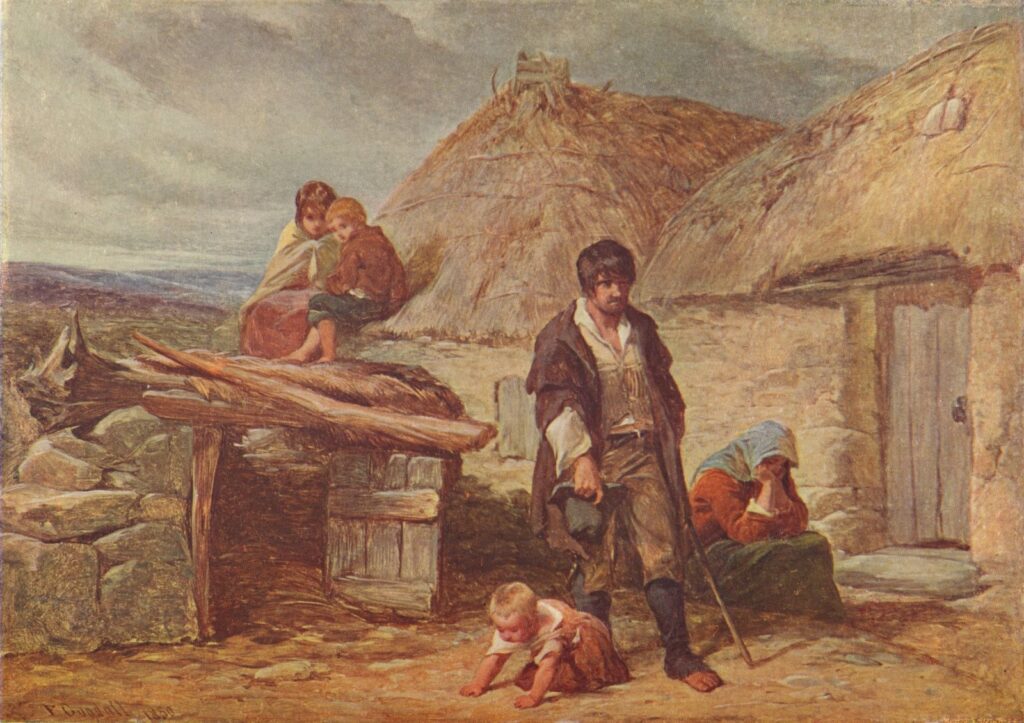

Tens of thousands of acres were handed over to English and Scottish colonists, who brought with them a new religion, new customs, and a fierce distrust of the native Irish. The dispossessed — the Irish-speaking Catholic peasantry — were driven to the hills, stripped of status and often of shelter.

Two Worlds at War

In town after town, in county after county, a new order was imposed. The Irish were reduced to tenants on lands they had once owned for generations — if they were allowed to remain at all.

Churches were claimed, ancient woods cleared, and walled towns rose where once there had been only pasture and stone cottages. In places like Derry, renamed Londonderry, Irish identity was not only suppressed — it was systematically replaced.

But the Irish spirit would not go quietly.

Whispers of rebellion grew in the shadows. Songs carried grief and defiance across the valleys. Language clung on like moss in the cracks of empire. And in 1641, the Irish rose.

Blood and Fire: The 1641 Rebellion

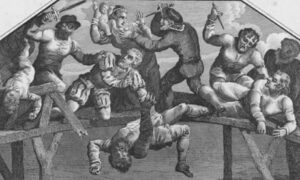

The Irish Rebellion of 1641 was a fury long fermented — a desperate attempt to reclaim land, dignity, and belief. Irish Catholics rose against the Protestant settlers, and violent reprisals followed. The country descended into a bloody struggle marked by atrocity on both sides, but at its root was the question that would haunt Ireland for centuries:

Who owns this land? And who has the right to say who belongs on it?

What followed was not liberation, but further devastation. The Cromwellian conquest of the 1650s crushed resistance with ferocity. Towns were massacred. More land was confiscated. The words of Oliver Cromwell echoed like a curse across the island: “To Hell or to Connacht.”

Legacy of Division

The Plantation of Ireland was no mere land grab. It was the imposition of a foreign identity — a campaign to dismantle a culture and displace a people.

Its scars are still visible today. The deep-rooted divisions in Northern Ireland — between Catholic and Protestant, nationalist and unionist — trace their ancestry directly to these forced settlements. The bitterness, the mistrust, the longing — all seeded in soil taken by force.

A People Unbroken

Yet, through it all, the Irish endured. Gaelic traditions survived underground. The language whispered on. Music, poetry, and myth outlasted gunpowder and decree. And the land — battered, bloodied, but beloved — remained the sacred heartbeat of a people determined never to forget.

The plantations failed in one essential mission: they could never sever Ireland from the Irish.