Belfast, December 1961. The bitter cold of a Northern Irish winter settled like a shroud over Crumlin Road Gaol, its dark, granite walls silent witnesses to decades of suffering and justice — and now, to its final execution. Behind those walls, a young man waited, alone, knowing that at dawn the rope would drop. His name was Robert Andrew McGladdery, and he was just 26 years old. At 8:00 a.m. on December 20, 1961, he would become the last person to be hanged in Northern Ireland.

This is the story of his fall from ordinary life into infamy — a tale of deception, obsession, and a brutal killing that shook a tight-knit community to its core.

The Innocent and the Obsessed

Pearl Gamble, a 19-year-old, lived with her family in the rural outskirts of Newry. Described by neighbors as gentle and full of promise, she worked as a shop assistant and cherished the simple joys of life — music, family, dances on Saturday nights. On the evening of January 28, 1961, she donned her finest dress and walked with friends to a dance at the Henry Thomson Memorial Orange Hall.

There, amid the flickering lights and the hum of records spinning on a gramophone, she danced and laughed. She had a boyfriend that night. But also in attendance was Robert McGladdery, a distant cousin, a quiet man with a brooding presence. Pearl had danced with him once or twice, perhaps out of politeness. She couldn’t have known that the man watching her with quiet intensity had grown increasingly obsessed — and that her kindness would soon be met with horror.

The Vanishing

The dance ended in the early hours of Sunday morning. Pearl was dropped off near her home, but when morning broke, her bed remained untouched. Her mother, worried but hopeful, assumed she had stayed over with a friend. But hours passed. Anxiety grew. Calls were made. By afternoon, the facade of normality cracked open.

Then came the call no mother should receive: a young boy, playing near the fields close to the Damolly crossroads, had stumbled upon a bloodied brassiere and a pair of shoes. The police descended quickly and soon discovered Pearl’s body in a secluded field. She had been beaten, stabbed, strangled, and partially undressed — an act of cruelty that bespoke rage and intention.

The community recoiled in grief and fear. Who could have done this?

The Web Tightens

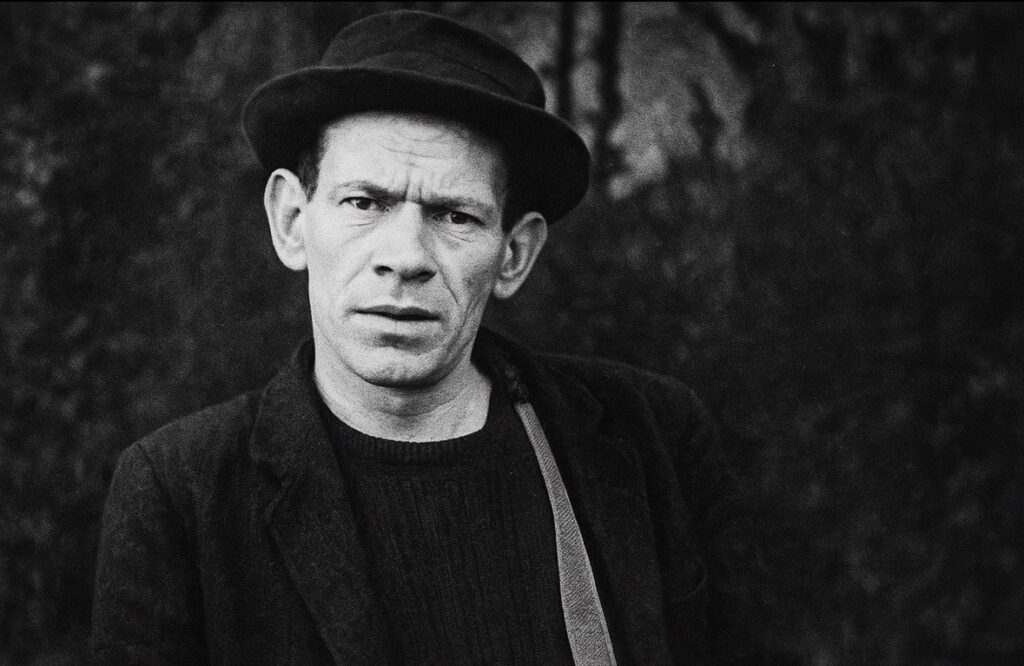

From the outset, suspicion turned toward Robert McGladdery. His behavior after the murder raised eyebrows. He claimed to have left the dance alone, wearing a dark suit. But witnesses contradicted him, recalling him dancing in a light-colored suit, and leaving after Pearl — not before. Even more damning, his manner seemed off: oddly controlled, eager to establish alibis no one had yet asked for.

The police placed him under surveillance. Days later, officers observed him slipping into woodland, returning empty-handed. Investigators retraced his path and unearthed a gruesome cache: a waistcoat, overcoat, and handkerchief — all soaked in blood. He had buried them under tangled roots and damp soil, desperate to erase the truth. But the land does not forget.

In the final act of concealment, McGladdery had hidden his bloodstained clothing deep in a septic tank near his home — a metaphor, perhaps, for the darkness festering within.

He was arrested, charged, and denied it all.

The Trial

The trial of Robert McGladdery began in Downpatrick Crown Court, drawing crowds from across County Down. The courtroom, heavy with silence, watched as McGladdery — slender, pale, and emotionless — stood in the dock and pleaded not guilty.

His defense insisted on coincidence, on mistaken identity, on circumstantial evidence. But the jury saw otherwise. The trail of lies, the bloody clothing, the motive born of rejection — it painted a picture too vivid to ignore.

After just 40 minutes of deliberation, the verdict was delivered: Guilty.

Presiding judge Lord Justice Curran, his voice solemn, donned the traditional black cap and sentenced McGladdery to death by hanging.

Crumlin Road Gaol

Crumlin Road Gaol — the dark heart of Belfast’s justice system — had seen its share of executions. But in 1961, capital punishment was falling out of favor. The public mood had shifted. Yet the law still stood.

Inside the cold, damp walls of the condemned man’s cell, McGladdery waited. Appeals were filed and denied. Rumors swirled. And then, the night before his scheduled execution, he made a stunning confession — not to the public, not in court, but to the prison chaplain.

Yes, he admitted, he had murdered Pearl Gamble. He had followed her after the dance, confronted her in the night, struck her down. He could not bear her rejection, nor her joy with another man. His crime, he said, was born of shame, fury, and a need to control what he could not possess.

The Final Walk

On the morning of December 20, 1961, as the sky barely began to lighten over Belfast, Robert McGladdery walked his final steps down the narrow passage to the gallows. Executioner Harry Allen, one of Britain’s most experienced hangmen, carried out the sentence with grim precision.

At exactly 8:00 a.m., the trapdoor opened. McGladdery dropped. The silence returned.

His body was buried within the prison walls, as was customary. A plain, unmarked grave. No plaque, no epitaph.

Legacy of a Crime

The murder of Pearl Gamble remains one of Northern Ireland’s most chilling tragedies — not only for its cruelty but because it marked the end of an era. McGladdery’s hanging was the last legal execution on Irish soil. Within years, capital punishment would be abolished.

Crumlin Road Gaol, now a museum, tells the story with haunting reverence. The cell where McGladdery spent his last night remains preserved. The execution chamber is still. Visitors speak in hushed tones, confronted by the weight of justice — and its final breath.

For some, McGladdery’s end was justice served. For others, it was a glimpse into a time when the state wielded life and death with solemn authority. But for all, it remains a haunting tale of how obsession can curdle into violence, how a moment of rage can rip lives apart — and how one name, now etched in history, stands as a final punctuation mark on Ireland’s era of execution.

“She smiled at me, and I killed her.”

— From Robert McGladdery’s reported confession, December 1961